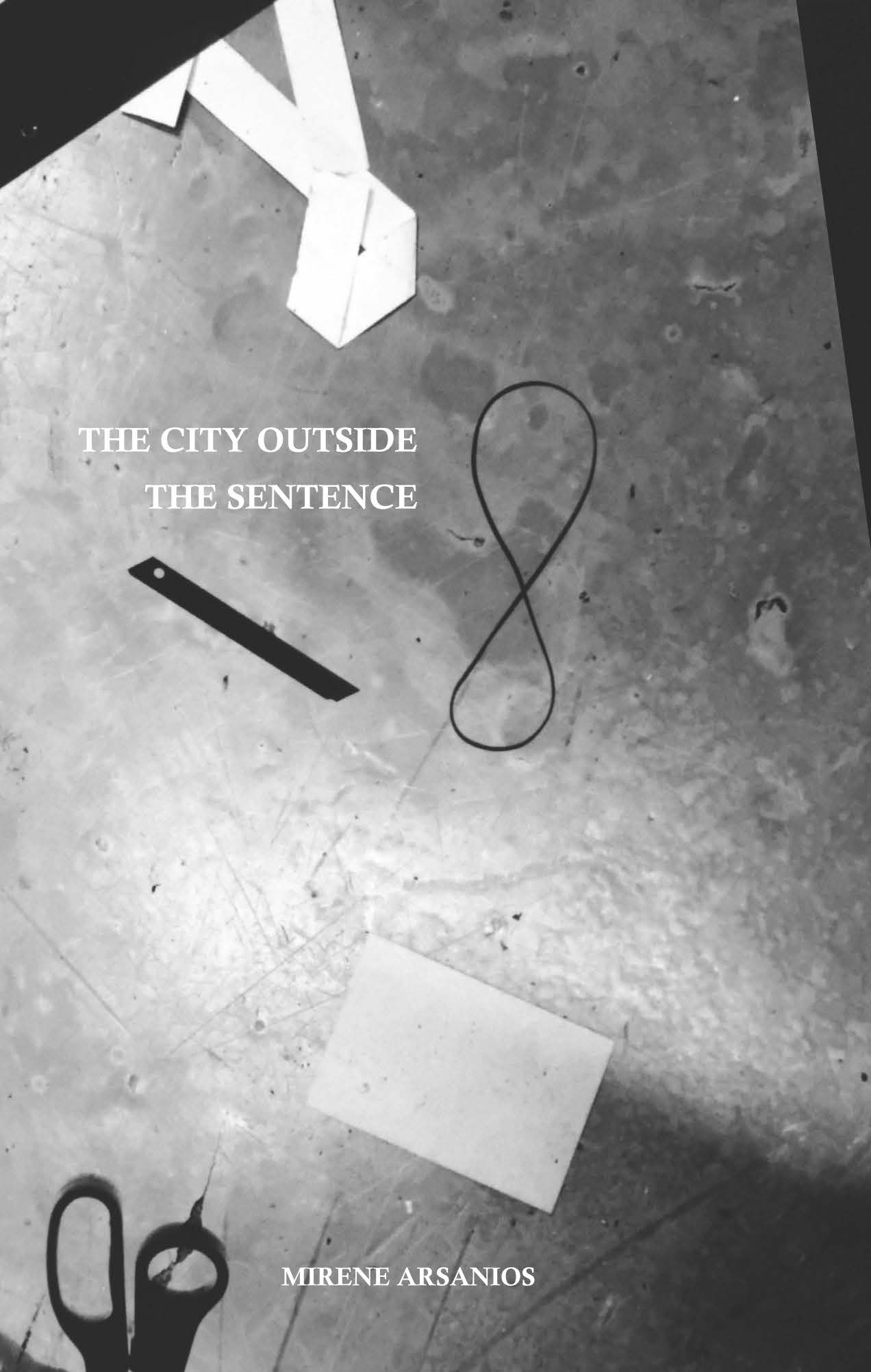

The City Outside the Sentence

Transitive and intransitive, of uncertain origin

I itch when I know a word but can’t pronounce it. To show that I know I can’t pronounce it, I smile. The person facing me smiles too, she knows I’m making an effort. When I force myself to pronounce a word I can’t pronounce, I drink water. Mistakes gurgle in water.

A few years back, in language classes, I wrote words the way I heard them. I was in love with my teacher. She had dark brown hair, closer to black than to brown. She ended every class with a new verb. In the last class she taught us the verb to rub, which means, “to move one’s hand or a cloth repeatedly to and fro on the surface.” She looked at her students and asked if anyone had a question.

“Can I rub my hand on a cloth?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said. “As long as you repeat the movement, you can rub different things together.”

At night, words come to me and I let them in. I stand close to them, like a wall stands in a room. The floor in the room was newly sanded. Everything lies under a blanket of wood dust, which makes words slower than they usually are. They trudge towards the object they signify without ever reaching them. The word SCREEN dabbles in the SINK and the word WINDOW barely reaches the windowsill. It stops and looks outside itself, through the opaque glass. My tongue is still a TONGUE, though it is covered with a patina of aging bacteria, dead words I like to pet then swallow.

To use the verb to rub, I smear some anti-itch cream on my forearms, then on my notebook, over the definitions. I worry the pages won’t absorb the cream and the benefits will be lost. The same loss I feel when I’m talking to someone without getting through to her, like blocking my anus with an upward pull.

When I’m in a conversation with my teacher I sometimes pause for no reason. That confuses her. I blame it on my pronunciation. When I lose my words and feel my blood boiling, I step outside my feeling and observe it. Instead of feeling sorry for myself, I feel sorry for the teacher.

I’m meeting her in a few hours, on Mournot Street. I’m excited to see the teacher after years of using the verb to rub. I feel nervous. I would like to turn the lights off to conceal the dark rings under my eyes, but I’m outside, on the street.

She looks fine, the teacher, slightly tired. She’s wearing a grey sweater with a scooped neck. Her shoulders look warm, still tanned from the summer. I want to rub her back. We decide to walk against the traffic. I would rather say nothing than say something she wouldn’t understand, although by now, I should be speaking the language I’ve been learning without mistakes.

The teacher seems happy to see me. She says she’s proud of me. I avoid asking for what; she is obviously proud of me for being her student because there is nothing else to be proud of, besides the suspension of judgment I’m capable of—ephectia—when it comes to the things I do. Since she too decides to be silent, I take the plunge and tell her about something that happened to me not so long ago. I decide to narrate the encounter as if it were a story:

The other day I saw three girls. Two were sitting on a stoop, one was standing. She talked loudly, as if addressing a crowd. Instead of looking at the other girls, she looked at the sidewalk. She was wearing a short leather jacket. The skin on her stomach was taut. It had been a while since I’d seen skin like that. She had a ponytail. She must have been thirteen or fourteen. I couldn’t tell what her race was. My guess is that she was a Roma girl from Romania but she also could have been from Argentina, originally from Palestine. She had a few ripe pimples on her chin. There was something about her I couldn’t name. She wasn’t pretty. She changed. I was attracted by the way she sat on top of her being and shouted, “This is my being!” I walked by while she was changing. She looked at me, gave me the finger and told me to fuck off.

The teacher laughs. She says it’s a great story.

“Did you?” she asks.

“What?”

“Fuck off.”

Of course I did, but I don’t tell her. I don’t want her to think that I’m weak like that. The truth is, I left speechless and the girls started laughing. As I walked away, their laughter grew louder.

I’m itching again. I am angry at my own symptoms. I feel a sudden desire to clean my hands but there is nothing I can use besides the sidewalk. I bend over and touch it without bending my knees, a condition I have set for myself and must abide by. I brush my hands against the pavement. The teacher looks at me, her body leaning on her left hip. When I lift myself up, blood reddens my cheeks. She’s proud of me, the teacher repeats. I smile and ask if she has water, take a few gulps from the bottle she hands me, and before giving it back, I gargle, exhaling through the liquid. The teacher and I silently walk to the bus stop. I’m glad it’s getting darker. To say goodbye, I rub my hand against hers.